Gisella Perl: The Abortionist of Auschwitz

Note: This is a difficult story. It contains descriptions of violence, torture, and genocide.

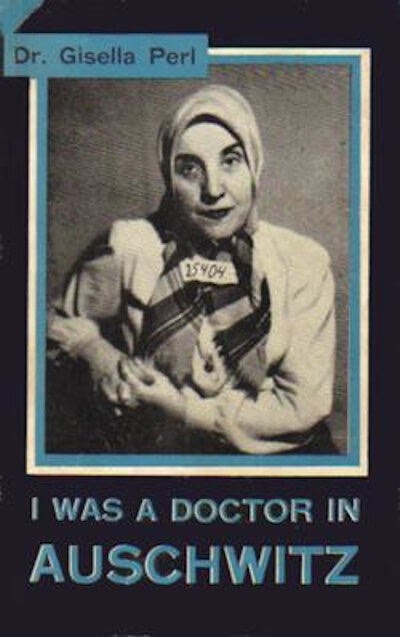

In Gisella Perl’s memoir, I was a Doctor in Auschwitz, she describes the small secret games prisoners would play together. Huddled in the dark, stripped of everything it was possible for one person to take from another, the women of Auschwitz played a game called “I am a lady.” Turn after turn, they told each other stories of their pasts and dreams for their futures, each beginning: “I am a lady.”

Perl shared her own contribution to the game, whispered into the ears of starving women wearing lice-infested rags inside a death camp:

“I am a lady- a lady doctor in Hungary. It is morning, a beautiful, sunny morning and I feel too lazy to work... I ring for my assistant and tell her to send the patients away, for I am not going to my office today… What should I do with myself? Go shopping? Go to the hairdresser? Meet my friends at the café? Maybe I’ll do some shopping. I haven’t had a new dress, a new hat in weeks…”

Perl depicts the horrors of Auschwitz with unflinching clarity: the physical depravations, the loss of freedom, the mass murders and torture. She also exposes the deepest perversion of the Nazi death camps, the worst potential outcome for its surviving victims. Auschwitz was designed to transform its inmates into what the Germans claimed them to be: subhuman. In unthinkable conditions, facing the most horrifying of choices, inmates devolved into theft, prostitution, even murder. Having torn from its victims every possession, every personal tie, every life-sustaining or supporting aid, Auschwitz tried to take their fundamental humanity. And how can any sane observer, staring into that abyss across the span of time, find blame?

But despite the conditions, Perl and the women around her found a way to keep a sense of self. Throughout her memoir, Perl spotlights individual women and girls who fought back. Not with weapons, as they had none; not even with words, at least not directed towards their captors. And sometimes, not successfully. But they fought back with spirit, with a refusal to see themselves as the Nazis painted them and pushed them to become. Night after night, in darkness and filth, they reminded themselves: I am a lady. I am a person. I am human.

Before the war, Gisella Perl was a lady doctor in Hungary: the only woman, and the only Jew, to graduate from secondary school in her small hometown. She studied medicine in Berlin because, at the time, the city had a particularly large population of Jewish doctors. She spoke Hungarian, Romanian, German, French, and Yiddish. She worked as a gynecologist alongside her husband, Ephraim Krauss, who was a surgeon, and together they had two children. She played the violin.

Before the war.

“Obliterate the biological basis”

In March of 1944, the German army invaded Hungary. Perl and her family, like the rest of the country’s Jewish population, were forced into an overcrowded ghetto where they hoped they might stay until the war’s end. By then, it was clear that worse fates than the ghetto were possible. But within months, the family was in a cattle car traveling towards Auschwitz where they were met with “the smoke of the crematory… the air full of the nauseating smell of burning flesh.”

The 400,000 Hungarian Jews who arrived that year to Auschwitz were sorted as they came through the gates, first women from men, and then life from death. Joseph Mengele, the camp doctor who would later come to symbolize for the world the worst atrocities of the Holocaust, stood at the front of the line ordering people to the right, towards the rat-infested barracks and a temporary chance at life, or to the left, towards the crematories.

Perl, along with four other doctors and four nurses, was ordered to establish a hospital for the camp. They treated everything from broken bones to broken skin, from tuberculosis to typhus. It was medicine without medication, without instruments, without even basic nutrition or running water. Perl lanced abscesses and set bones without anesthetic. With no ointments to help relieve the rashes and sores resulting from parasites and poor hygiene, she started using the margarine from their meager dinner as a salve to cover the wounds. And when nothing else was possible, she talked with her patients, reminding them of the past and painting for them the possibility of a future.

Early in her time at Auschwitz, Mengele ordered Perl to report any pregnancies directly to him. These women, he said, would go to a different camp and receive double rations. Many prisoners, desperate to escape starvation, rushed to declare their pregnancies. Perl discovered the lie when she witnessed a group of pregnant women being beaten and attacked by dogs before being thrown alive into the crematorium.

The goal of Auschwitz, as camp commandment Rudolf Hoess recorded in his autobiography, was no less than to “obliterate the biological basis of Jewry.” An infant was a potential future; a fertile woman, a threat. Initially overwhelmed by what she saw, Perl recalls that “gradually the horror turned into revolt,” and she made the decision that no more pregnancies would be revealed to the Nazi doctor.

The decision was heroic in its aim and gut-wrenching in its execution. Many women arrived at the camp already pregnant; others became pregnant through prostitution or what Perl delicately called “love” with guards or prisoners. When Perl found that a woman was expecting, she explained what discovery would mean: a painful death for the baby and the mother. She then helped the woman to conceal, and eventually terminate, the pregnancy.

For women who were only a few months along, she manually dilated the cervix to remove the fetus with her fingers— an operation done “in the dark, always hurried, in the midst of filth and dirt.” The mother’s abdomen was bandaged, and she went back to roll call the next morning. For women who were closer to delivery, she ruptured the membranes (caused the water to break) to accelerate spontaneous delivery. If the child was stillborn, she buried it among the heaps of corpses that littered the camp. If the child was born alive, she had a harder task.

She is unflinching in her recollection of an infant, born alive, who she knew faced torture and experimentation if discovered:

“I took the warm little body in my hands, kissed the smooth face, caressed the long hair- then strangled him and buried his body under a mountain of corpses waiting to be cremated.”

Pregnancy in Auschwitz was a death sentence. By ending pregnancies, she offered the mother a chance “to come out of this death camp not only alive but in a condition to have other children — later.”

“You owe me a life, a living baby.”

Seven months after her arrival, Perl was sent away from Auschwitz- potentially because of her intimate knowledge of Mengele’s torture chamber laboratories and what occurred there. She was transferred to Bergen Belsen, a place that was even more horrific:

“Bergen Belsen can never be described, because every language lacks the suitable words to depict its horrors. It cannot be imagined, because even the most pathological mind balks at such a picture. One must have heard those unearthly screams of agony which continued through the day and the night, coming from hundreds of throats, unceasingly, unbearingly…”

In this hellscape, Gisella Perl was put in charge of “Block III,” the maternity ward. With no equipment, no medication, no water, she treated hundreds of women. Starving, lice-infested, typhus-ravaged, the outcomes were rarely positive. “And yet,” Perl wrote, “the doctor in me never gave up even when the human being reached the limits of its endurance. I fought on with bare hands, cut my shirt into rags to wipe the hot, moist, soiled faces of my patients, tried to smile at them through the layer of filth that covered my own face.”

On April 15, 1945, Perl was in her maternity ward at Bergen Belsen helping Marusa, a young Polish woman from the Warsaw underground movement, give birth. Around them, the camp buzzed with rumors of liberation. The allies are coming! Will the Germans destroy the camp, with all of us in it, to destroy the evidence of what they have done? Or is freedom within reach?

As the British forces entered Bergen Belsen, Marusa’s baby offered up its first screams of life to mingle with the cries of thousands of newly liberated prisoners. The first free child of the camp was born. But Marusa was hemorrhaging dangerously, and Perl lacked even the most basic tools to stop the bleeding. She ran from the tent to beg the arriving troops for water, for disinfectant, for help. Supplies in hand, she returned to perform a hysterectomy on her knees, in the dirt, with battle-hardened Brigadier General Glyn Hughes kneeling beside her, tears running down his face. Marusa and her baby survived Bergen Belsen.

After the war, Perl testified to the Nazi atrocities she had witnessed and experienced, raising money for survivors and refugees. “I didn’t want to be a doctor,” she confessed, “I just wanted to be a witness.” She credited Eleanor Roosevelt with releasing her back into the world. After one of Perl’s lectures, Mrs. Roosevelt invited her to lunch and urged her: “Stop torturing yourself; become a doctor again.”

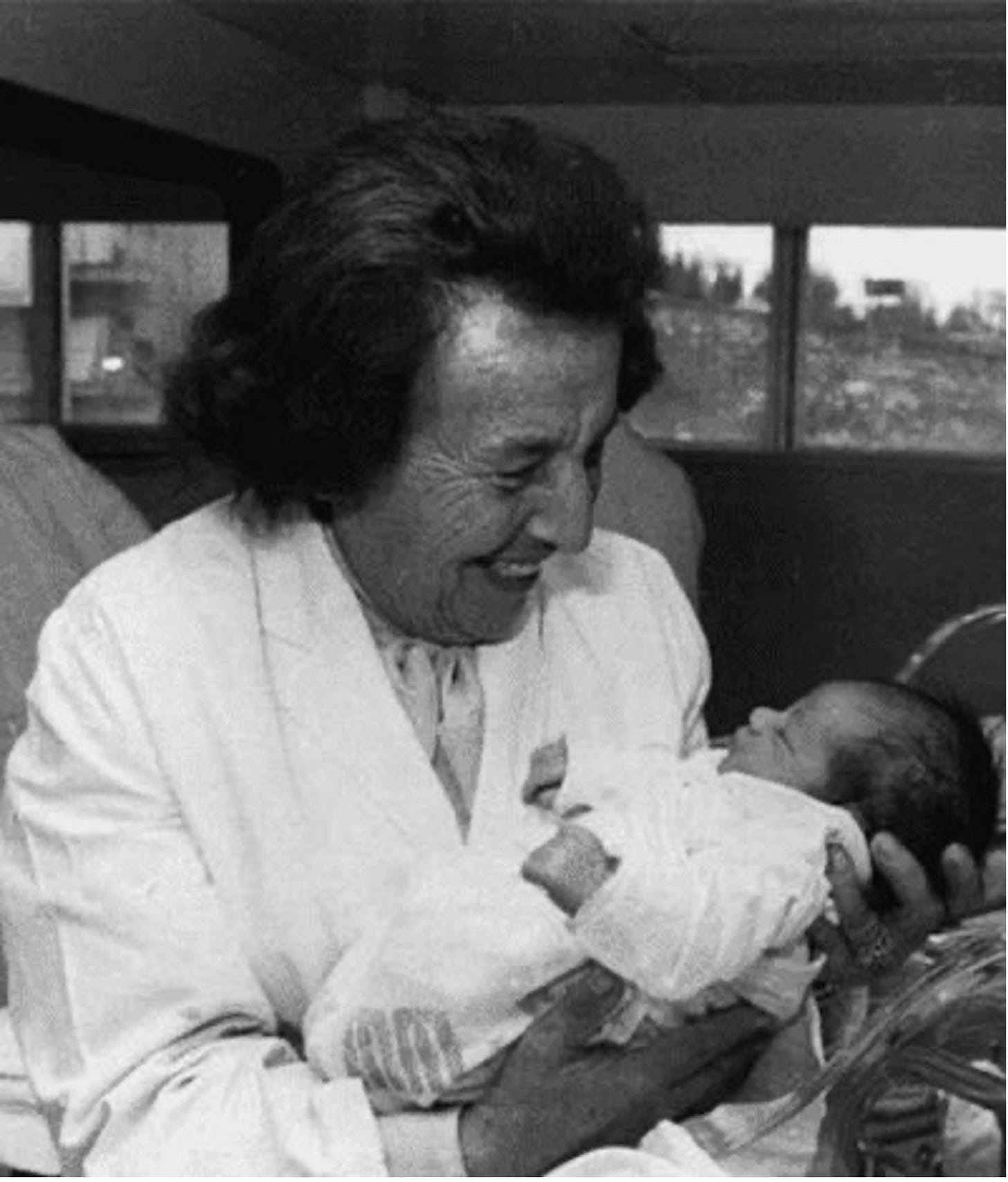

Perl was granted US Citizenship in 1951, and set up a practice at Mount Sinai Hospital as a gynecologist specializing in infertility. When she discovered that her daughter was still alive, she moved to Israel with her and worked at the Shaare Zedek Medical Center in Jerusalem. She practiced another 43 years, until her death in 1988, delivering roughly 3,000 healthy babies after the war. And every time she entered a delivery room, she offered the same prayer.

“God, you owe me a life. A living baby.”