He touched the thyroid

Emil Theodor Kocher: Part 2

In the 1800s, surgical success was very much defined as getting the patient off the table. The really ambitious surgeon aimed for getting patients out of the hospital. Kocher had changed what was considered possible— but he hadn’t changed the definition of success. Not yet.

So what was wrong with Maria? She had no bleeding or infection after her surgery, and she was still alive a decade later. But she wasn’t doing well. Her growth was stunted, she was short and stocky. Her intellectual abilities, once normal, were now severely limited. Her face had taken on a heavy and swollen appearance. Kocher was asked: is there a chance that your operation caused this change in her?

Conservative opinion of the time was a definitive NO. Others had noticed a possible connection between the thyroid and a collection of symptoms that included growth retardation. But it was rarely reported, sometimes disbelieved or dismissed as a coincidence, and in those who did see a connection, assumed to be the end-stage result of the original thyroid disease. In other words, the thyroid was clearly diseased and had become enlarged as a goiter. Taking it out should have prevented these symptoms, but if you see them anyway, maybe you operated too late.

French physiologist Claude Bernard described it this way in 1879:

We know absolutely nothing about the function of the [thyroid], we do not even have an idea of its utility and of the importance it may have, for its removal has not told us anything about this, and anatomy alone remains absolutely silent.

The thyroid is widely believed to be useless in health, and dangerous only when diseased. And its removal— if technically possible— should be pursued.

So what does Kocher do when he gets this message? He told the story very plainly in his own words, looking back:

It was the influence of just one case, on whom I had operated in 1874 (that changed my opinion on the nature of the thyroid) and about whom a doctor mentioned that the girl in question had since undergone a complete and substantial change in the nature of her character. This was so important to me, that I now took all pains to see the girl with my own eyes. I was astonished to a great extent by the conspicuous looks of the individual in question. I immediately sent invitations to all my patients on whom I had operated for goiter asking them to present themselves for examination.

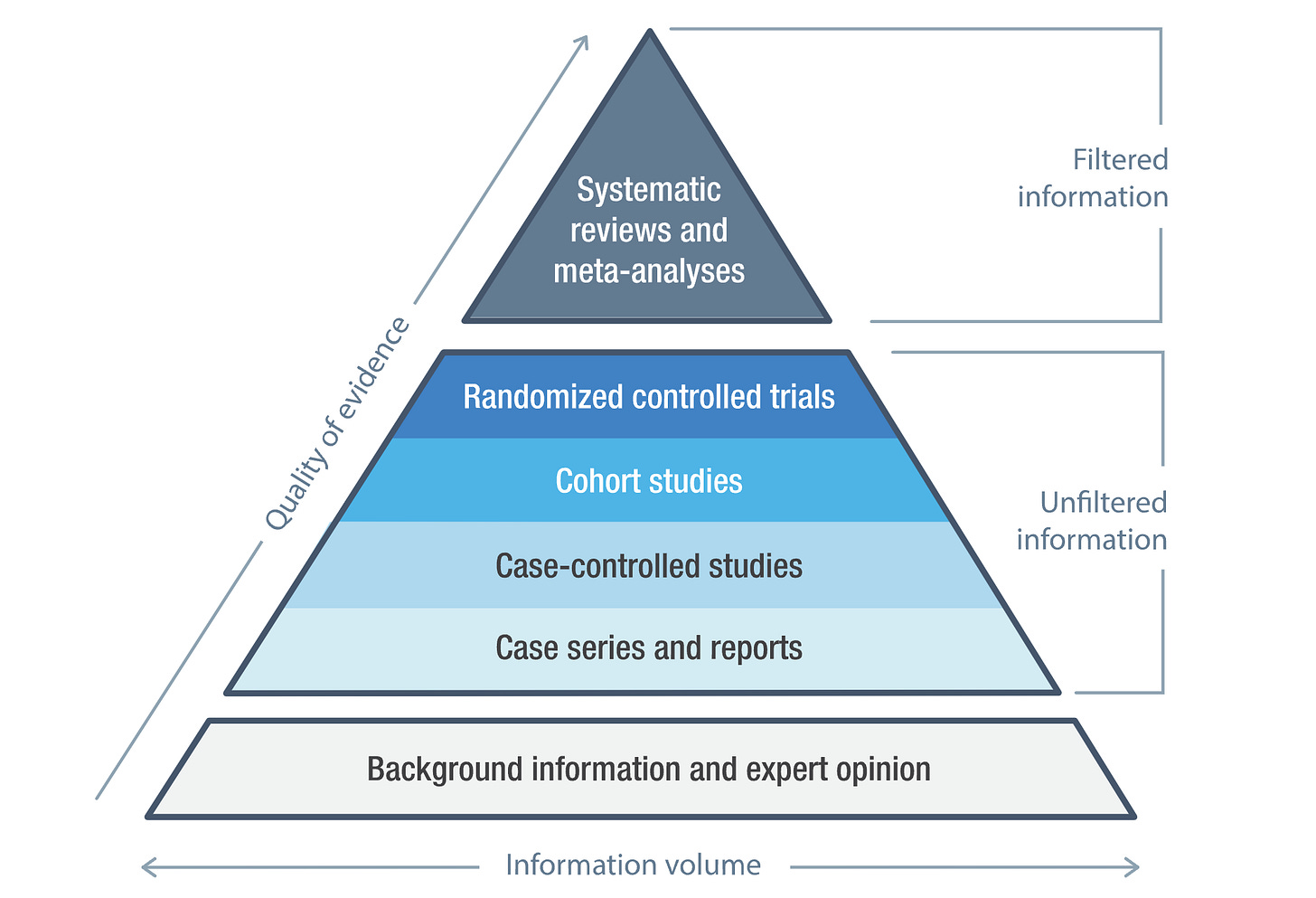

This is what’s known as a “single surgeon case series.” Today, it’s the lowest level of clinical evidence: it’s one step above an anecdote, because it’s a series of anecdotes. In the 1800s, it was a nearly unheard-of level of review.

Surgeons in the 1800s were not looking back on their cases for long-term outcomes. The goal of a surgeon was to finish the operation. His patients left the hospital. From what he knew, they were happy and healthy and living their lives. To ask people, sometimes years later, to come back and see how they were getting on is an appreciation of physiology that is completely novel in medical history to this point. Kocher’s response was an epistemological landmark in a field that needs epistemology badly. It was the recognition that what was thought absolutely true yesterday— the thyroid does not have a necessary function— must immediately be called into question today upon the appearance of new data.

Kocher sent invitations to his last hundred patients; 60 of them responded. Of 53 who were still living, 28 had only a partial removal of the gland. These patients, he reported, “enjoy the best of health and are very happy with and grateful for the success of the operation.” The results in 34 patients who had a total removal of the gland were entirely different: “Of the patients who presented themselves for examination, only 2 showed unchanged or improved general status.”

On April 4, 1883, Kocher reported his findings to the German Society of Surgery in Berlin. It was a long lecture, including a 15-page description of his findings and theories. He concluded that the thyroid clearly had a crucial function, describing it (somewhat poetically) as the task “to paralyze the influences which produce stupidity.” He published his list of patients. He described each of their features and outcomes in detail.

I imagine that he must have felt much like his students, at the bedside of a wound infection, desperate to beat his breast and exclaim, “I have sinned!” He wrote later:

In technical terms, we have certainly learned to master the operation for goitre. We can deal with bleeding and prevent loss of speech. But something else happened… removal of the thyroid gland has deprived my patients of what gives them human value. I have doomed people with goitre, otherwise healthy, to a vegetative existence. Many of them I have turned to cretins, saved for a life not worth living.

The Pursuit of Truth

A surgeon is a strange type of person. He or she must be willing to stake their livelihood, and someone else’s life, on their knowledge of the world. I used to tell medical students: there are no subjectivists in the operating room. Anyone who has held a scalpel knows that you cut, or you don’t; the structure bleeds, or it doesn’t. It is a thing, definite, and the consequences are apparent. You learn to trust your senses and your conclusions. You need to trust your own mind, because if you don’t, you become paralyzed, unable to act. Surgeons, it is said, are sometimes wrong— but never unsure. So what happens when the state of knowledge changes? When what was absolutely true yesterday is called into question today?

Ironically, it was probably Kocher’s unparalleled precision that allowed him to so clearly demonstrate the purpose of the thyroid. Other surgeons attempting to remove the thyroid gland were less absolute in their anatomy and their methods. Theodor Billroth, an equally famous name in the history of surgery, worked with Kocher on some of the technical and antiseptic advancements that enabled safe thyroid surgery. But when he followed Kocher’s example and reviewed the results of his own operations, he found a much lower incidence of symptoms. William Stewart Halsted, in his 1920 book on the history of goiters, explained the difference:

I have pondered the question for many years and conclude that the explanation probably lies in the operative methods of the two illustrious surgeons. Kocher, neat and precise, operating in a relatively bloodless manner, scrupulously removed the entire thyroid gland doing little damage outside its capsule. Billroth, operating more rapidly and, as I recall, with less regard for the tissues and less concern for hemorrhage, might easily have left fragments of the thyroid behind.

Kocher’s precision, his competence, his uncompromising dedication to excellence— his very merits— were what exposed his error.

He spent the rest of his career searching for an explanation for his findings. His ideas on the physiology and pathology of the thyroid gland caused controversy, as any new ideas must do. He did not discover thyroid hormone; that happened after his death. But he did experiment with oral and injected extracts of thyroid tissue as a treatment, an early precursor to transplantation and hormone replacement therapy. And he was adamant that surgeons should not remove the whole gland.

Importantly: he continued to operate, and he continued to operate on the thyroid. He completed more than 5000 thyroid surgeries in his career. After seeing Maria, he removed only half or three-quarters of the gland, noting that this partial removal resulted in no long-term consequences.

And he remained a giant in his field. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1909, in recognition of his work on thyroid physiology that eventually did lead to the discovery of thyroid hormone. Today, hormone replacement for hypothyroidism is common, and many types of thyroid cancer are completely curable with a total resection. For that, we thank Kocher.

And as we thank him, it’s worth reflecting on the nature of his accomplishments, which go beyond the technical or the anatomic. In his middle age, at the height of his career, Kocher faced the possibility that his life’s most important work to that point— the technical perfection of thyroid surgery— was causing disastrous harm. Rather than flinch from the possibility, rather than deny, deflect, or despair, he flew into action, with a need to understand that overrode all other considerations.

Kocher’s story, when it is told (usually in an operating room, by an endocrine surgeon, to either bore or entertain a medical student), is told as a story of achievement, advancement, and innovation. A timeline of discovery after discovery, invention after invention, a testament to meticulous attention to detail and a creative mind.

But his real contribution, which carries no eponym, is to medical epistemology: the study of how we know. It is the simultaneous ability to be so confident in your knowledge that you will stake lives upon it— and so aware of its limitations that you will question it in an instant, on a word. This is the true legacy of Emil Theodor Kocher, and it’s the one that you can take with you into whatever field you work in. Because all of us, in our own way, are doing new work, pursuing new insights, and developing new things. We all build a life upon our past work, build new knowledge on past knowledge. In medicine, new treatments give rise to new complications; in technology, potential innovations create new challenges; in culture, new movements surface new weaknesses.

In each of our lives, in our careers and our relationships, there may come a day when we discover that a premise or practice we’ve built our work and lives upon contains an error. Like Kocher, we may face the choice to bow our head, shaken by the depth and breadth of the potential fault. We may turn to cautionary tales of human fallibility. Or we might- like Kocher- reject both doubt and blind allegiance, and focus instead on an unflinching need to understand what’s actually true.

Kocher’s story is the story of all human progress. It is the story of a fallible human being who, through exacting methods, unremitting toil, and moral courage, improved our understanding of the world.

Stellar article Laura! Loved the story and the message. This is a bit nerdy, but I also loved how you structured it. How in the first part you started with Maria and her surgery, then moved to who Emil, and then to what thyroid surgery was like.

I was only planning to pop onto Substack for a couple of minutes, but got swept into your article (and the first part).

Your point about how Emil's real contribution is to medical epistemology, reminded me of a story about the psychologist Daniel Kahneman.

When he published his book Thinking Fast and Slow he had a whole chapter about priming. The study of how small changes in our environment influences our thoughts and behaviours. The classic study was when you show people words associated with the elderly (e.g. bingo, wrinkles, Florida) they walk more slowly down a hall because they have been 'primed'.

Not long after his book was published, the replication crisis hit psychology and we learned that priming studies didn't replicate. Basically his whole chapter in his mega best selling book was unreliable.

Thinking Fast and Slow sold heaps of copies, was read by famous people, was in airports around the world, and at the start of the priming chapter Daniel had said the evidence for priming was so strong we had no choice but to accept it.

How easy it would have been to double down and bite back against the critics? To deny that priming was probably not a thing.

Instead Daniel basically said "You're totally right, priming effects don't seem to be real".

Daniel, like Emil, wanted to improve how we understood the world. and he knew that to really do that he had to focus on getting things right not on being right.

“No one enjoys being wrong,” Daniel said “but I do enjoy having been wrong, because it means I am now less wrong than I was before.”