On the Motion of the Heart

In which William Harvey kills a pig, defies the church, and makes history

It’s 10am on April 17, 1616.

In the Royal College of Physicians in London, the 2nd annual Lumleian Lecture on Anatomy is about to begin. The speaker is William Harvey: a small, dark man with penetrating black eyes and a quick, vivacious manner. Despite his presence on one of the most prestigious podiums of the day, Harvey is actually only a junior Fellow in the College— younger and less esteemed than most of the learned professors and physicians who fill the first rows of his audience. And despite the fact that the lectures were traditionally delivered in Latin (a language that the lay public and indeed most surgeons at the time could not understand), the hall is packed with onlookers of every class who are drawn by rumors that the lecturer has strange views, and stranger methods.

Harvey is about to change the world. He is about to tell his audience that the Church, the venerable professors, and almost everyone in the College is wrong about the function of the heart, and the flow of blood in the body. He is about to reveal what medical historians will later call, “the greatest medical discovery of all time.” But to understand that discovery, we need to back up a bit and understand the era, the man, and the pivotal importance of what he’s about to do.

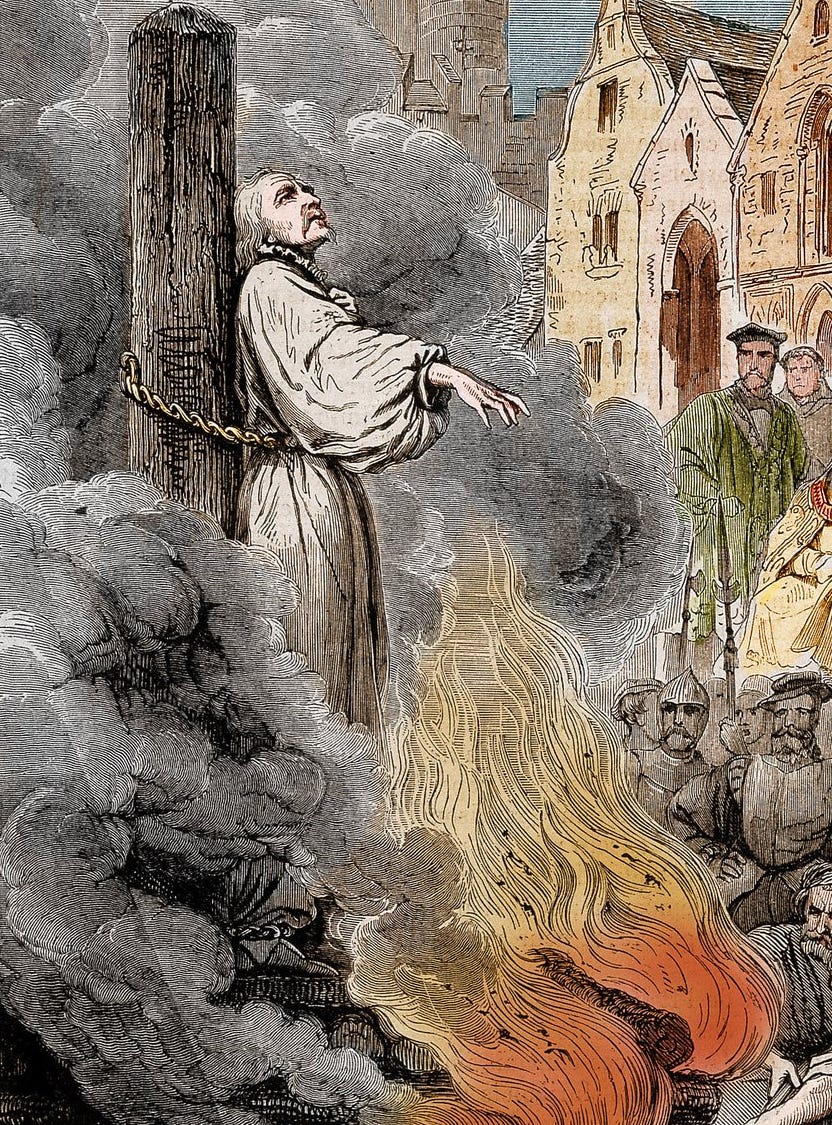

This is England during the Scientific Revolution. This is the Renaissance, the Enlightenment. It’s the century when Galileo will prove that the earth revolves around the sun, and Isaac Newton will describe the laws of gravity. But it’s also the century when Galileo is put under house arrest by the Catholic Church for his heretical theories. About 50 years before Harvey’s lecture, a man named Michael Servitus was burned at the stake as a heretic for contradicting the church’s teaching on the flow of blood. And it’s not just religion that impacts scientific progress: it’s also secular dogmatism. In all cultural areas, Europe— as it awakens from the Dark Ages— is looking with enchanted and deferential eyes to the past. The “rebirth” of the 17th century was not, initially, the creation of new art, culture, or philosophy. It was a renewed interest in, and emulation of, the art, literature, philosophy, and even science of classical antiquity.

What does this mean for medicine? It means the creation of the Cult of Galen. Claudius Galen, born in 131 AD at the height of the Roman Empire, was a physician to the emperors and a surgeon to the gladiators. He wrote extensively on human anatomy, producing hundreds of treatises. He also lived and worked in an era when human dissection was prohibited, raising the question: where did Galen get his data? Most likely, he had three sources. The first was other anatomists, either predecessors or contemporaries, including early Hindu and Chinese scientists. The second was likely his unique access to gaping wounds in the abdominal and thoracic cavities of the gladiators, giving him by dint of his position the ability to perform near-autopsies every week. The third source of data was that most commonly used by early anatomists: comparative anatomy. Galen performed countless meticulous dissections of pigs, apes, lions, dogs, and more— trying to determine which animal was closest to human for each body part.

Galen’s work led to real breakthroughs in understanding the human form. He was the first to describe many major nerves, for example, and he showed that urine was formed in the kidney, and traveled in tubes (ureters) to the bladder. He was also the first to discover the function of the heart: a pump to push blood through the arteries, those tubes that earlier anatomists believed carried air, rather than blood. But he also developed or perpetuated a number of misconceptions, some deriving from the differences between the animals he studied and the people he sought to describe. While his own observations on the function of the heart were a dramatic advancement, he still believed in the “pneumatic theory” of blood flow, handed down from Hippocrates. This theory argues that blood originates in the gut after each meal, then receives its vital force (the “pneuma”) from the liver, before heading back to the heart to be dispersed throughout the body. In other words, blood flows through the body in a one-way circuit away from the heart. It arrives at a final destination in the body (organs or limbs) and never travels back.

Galen was one of the most influential and prolific scientific writers of the Roman empire, and in the classical revival of the 1600s, his teachings were not simply rediscovered. They were canonized. One of his fiercest defenders was Jacobus Sylvius, a French anatomist. When presented with evidence of an error in Galen’s writings, Sylvius supposedly responded angrily:

“Then man must have changed his structure in the course of time, for the teachings of Galen cannot err!”

In 1616, both the Royal College and the Church had firm views on the nature of the heart and the flow of blood in the body. To question one was to commit secular heresy and risk career suicide; to question the other was to commit religious heresy and risk imprisonment or death.

And in that context, let’s return, to our unprepossessing lecture hall on a bright spring morning in 1616. William Harvey is about to take the stage— and dare both.

The Lumleian Lecture

Looking out on an audience who imbued theories on the flow of blood with both divine and political importance, Harvey must have known that he needed to overwhelm his audience with evidence. His lecture lasted the entire day. He referenced over 100 authors and performed a dozen experiments live on stage. The audience, largely, agreed with Galen and the pneumatic theory of one-way blood flow. Harvey told them they were wrong. And then he showed them.

First, he brought a live pig— squealing and thrashing— onto the stage. He took out a scalpel and slashed its neck, cutting first through the internal jugular vein, which resulted in a steady flow of dark mahogany. His next slash went through the carotid artery, spraying the stage with a geyser of brilliant crimson. With the two types of blood flowing in front of him, Harvey asked his audience: what explains the difference in pressure between the two types of vessels? Could it be, perhaps, that one system holds blood being forced away from the heart, pressured by each beat of the strong muscle, while the other more gently carries blood along the reverse journey?

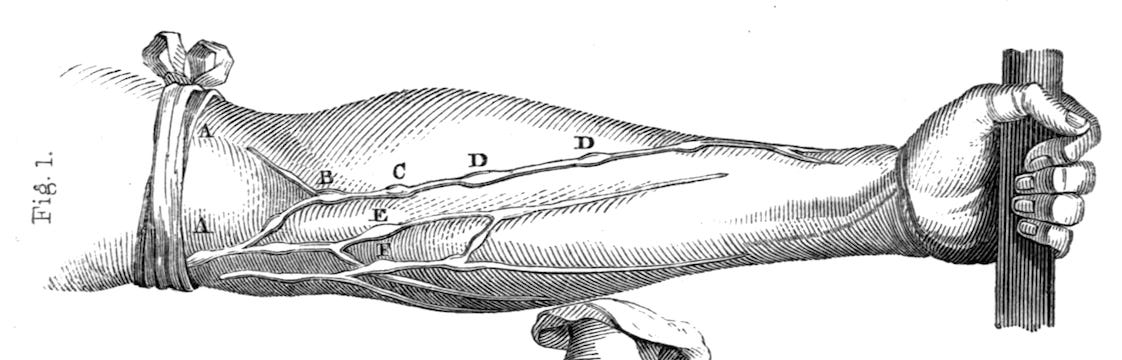

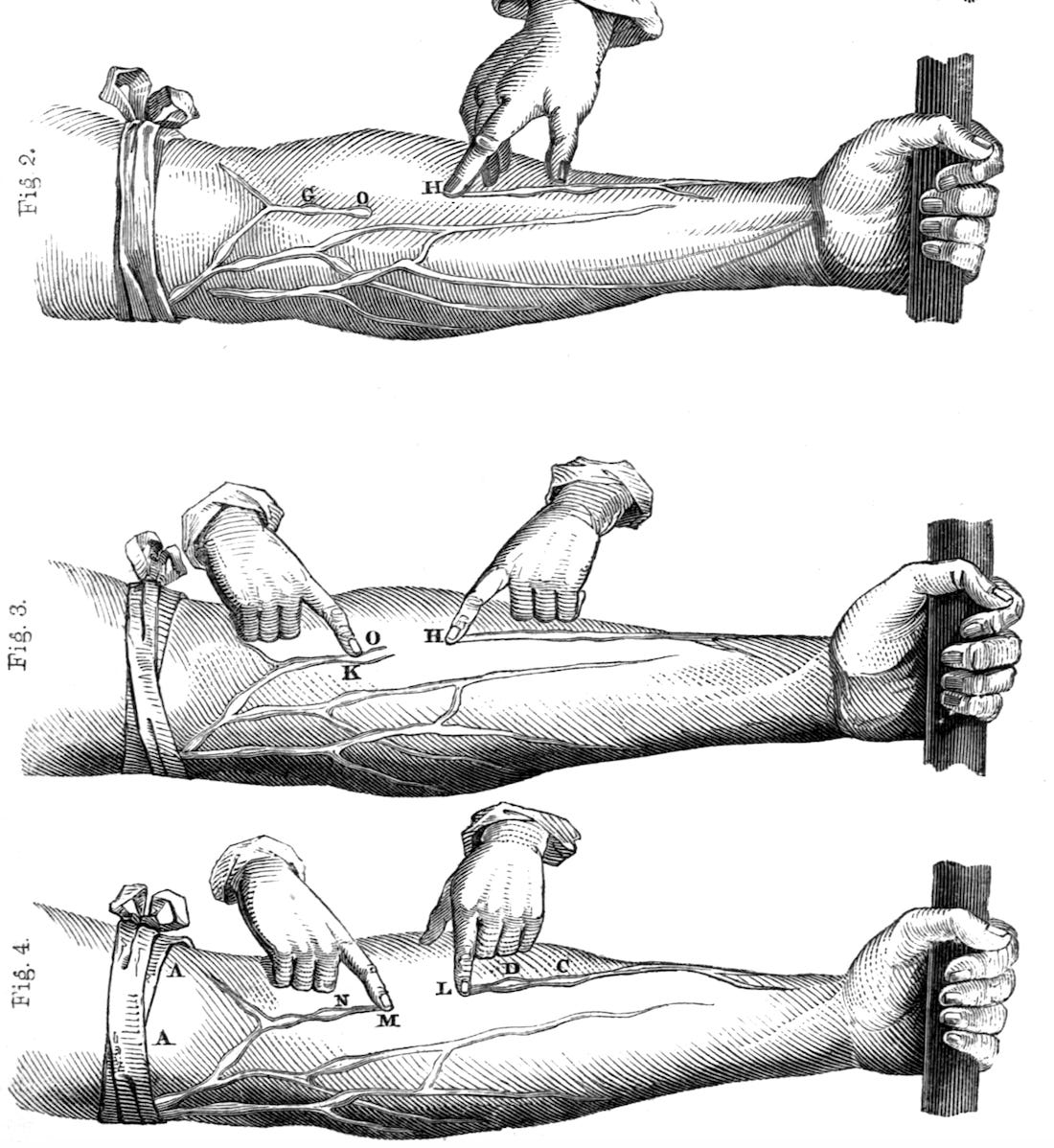

His next demonstration went further. He invited on stage a large man with muscular forearms and generous veins. Harvey tied a tourniquet around the man’s upper arm, causing his veins to bulge out even more dramatically (you can see this in your own arm, if you ever have your blood drawn at the doctor’s). First, Harvey asked the audience to observe that the veins were not uniform: there were irregular swellings along their length. Valves, he argued. The swellings had been observed and described by Hippocrates, among others, but their function was unknown in 1616.

Next, Harvey used his finger to gently compress one of the veins in the middle of the man’s forearm. When he pushed gently, the vein disappeared between the place of obstruction and the next valve as though emptied of blood. He then used another finger to coax the blood out of the vein and down towards the hand. He was able to “milk” the vein in this way and compress it, collapsing the vein all the way down to the hand. According to the pneumatic theory, the hand was the blood’s final destination. If blood flows in a one-way circuit, he had simply sped up its journey. But when he released his finger, a startling revelation occurred: the blood rushed back into the vein, filling upwards from the hand and towards the tourniquet! The blood flowed through the vein TOWARDS the heart!

Blood, Harvey declared in conclusion, flows in two directions! It flows with high pressure through arteries going away from the heart, and then it returns from the tissues in the low-pressure veins going back towards the heart. It was a conclusion that flew in the face of Galen and his followers, and a conclusion the church considered heretical. Harvey had, in one lecture, fundamentally changed our understanding of how the body works— laying the groundwork for centuries of advancements to come. The preface of the English version of his book (originally published in Latin as De Motu Cordis) described it thus:

Harvey was more blasé in his own reminiscences of the lecture, saying:

There were countless anatomic discoveries still to make after 1616, and some were made by Harvey himself. Others came from his students or the new schools that sprang up throughout Europe and the United States as anatomists shook off the shadow of Galen. The 1616 lecture— long, dramatic, and disturbing— was a first step towards many later advancements and discoveries. Its importance lies in its knowledge, true, but also in its methods. Harvey stepped on stage and defied his community, his country, his deity— in pursuit of truth. He put the observations of his senses and the conclusions of his mind above all else, and in return, he ushered in a new age: The Age of the Anatomists.

“In departing from any settled opinion or belief, the variation, the change, the break with custom may come gradually; and the way is usually prepared. But the final break is made, as a rule, by some one individual, the masterless man of Kipling’s splendid allegory, who sees with his own eyes, and with an instinct or genius for truth, escapes from the routine in which his fellows live. But he often pays dearly for his boldness.”

- Sir William Osler, describing William Harvey in the 1906 Harveian Oration at the Royal College of Physicians

Fascinating!